With Gladys’ two week lockdown now entering its twelfth week, and no end in sight (at least for us), we are going to spend some time exploring the Psalms. We should observe from the outset that the Psalms are not meant for study, they are meant to be recited, memorised, experienced.

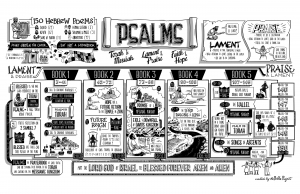

Psalms is one of the longer books in the Bible,* consisting of a collection of 150 songs, poems and prayers from Israel’s worship. The word ‘psalm’ comes from the Greek word psalmos, meaning ‘song’. In Hebrew, they are called Sepher Tehillim, meaning ‘book of praises’.

Authorship

The Psalms were written by various authors and represent different periods of Israel’s history. Seventy three psalms are titled ‘Psalm of David’ (3-41), and are widely accepted to be the work of Israel’s great king. Two were authored by Solomon (72, 127), twelve by Asaph, Samuel’s grandson and David’s worship director (50, 73-83), one each by Heman (88), another grandson of Samuel and David’s seer and Ethan (whoever he was). Another eleven psalm were written by the sons of Korah. Psalm 90, attributed to Moses, is thought to be the oldest. About a third of the psalms are unattributed. There is no way to know whether these psalms were actually written by these authors or were written in their honour.

Most of the Psalms have introductory information that is now widely recognised as being ancient and authentic.

Genre: Types of Psalms

Hermann Gunkel (1862–1932), the great German scholar, pioneered form criticism of the Psalms, identifying five different literary types:

- hymns of praise; (8**; 19.1-6, 33; 66.1-12; 67**; 95; 100; 103; 104; 111; 113; 114; 117; 145-150) including songs of Zion (46; 48; 76; 84; 87; 122); and enthronement songs (49, 93, 96-99);

- community laments (12; 44; 58; 60; 74; 79; 80; 83; 85; 89**; 90; 123; 126; 129);

- individual laments (3; 4; 5; 7; 9-10; 13; 14; 17; 22; 25; 26; 27; 28; 31; 36; 39; 40:12-17; 41; 42-43; 52; 53; 54; 55; 56; 57; 59; 61; 64; 70; 71; 77; 86; 89**; 120; 139; 141; 142);

- songs of thanksgiving (8, 18, 19,29, 30, 32-34, 36, 40, 41, 66, 103-106, 111, 113, 117, 124, 129, 135-136, 138-139, 146-148, 150);

- mixed types such as wisdom psalms (1; 36**; 37; 49; 73; 112; 119; 127-128) royal psalms (2, 18, 20-21, 45, 47, 68, 72, 89, 101, 118, 132, 144), songs of ascent (120-134).

Gunkel’s work focused on finding a life setting for the psalms within Israel’s worship. His work was extended by Sigmund Mowinckel (1884–1965) who sought to tie each psalm to a liturgical calendar, but probably got a bit carried away.

It would be easy to get lost in the weeds here, but two other scholars give us much simpler schemes. Westermann argues that all of the psalms swing between two poles: lament and praise.

Brueggemann, building on Westermann’s work classifies the psalms in three groups:

- psalms of orientation, (creation, Torah, wisdom, retribution, well-being)

- disorientation (personal and communal lament) and

- new orientation (individual and communal thanksgiving, royal/enthronement, psalms of confidence, hymns of praise).

Structure and Arrangement

It is easy to mistake the psalms for a random collection of songs and prayers with no logic or order in their arrangement. Pick one that takes your fancy; read it aloud. Nothing could be further from the truth.

The Psalms are carefully arranged into five books which are probably intended to mimic the five books of Moses. Each book has an internal arrangement and an overall message. The Psalms retell the story of God’s dealings with the people of Israel and especially the house of David and look forward to the coming of the Messianic King. Here is a brief sketch.

Two psalms introduce the Psalter: a wisdom psalm (Ps 1) that contrasts the righteous and the wicked; and a Royal Psalm (2) that underlines God’s sovereignty over the nations. Then come the Five books. with five hallelujah psalms (146-150) to conclude the collection.

The esv.org resource page gives an excellent outline of the structure of the five books:

| Book 1 | Psalms 1–41 | Psalms 1–2 provide an introduction to the Psalms as a whole. Except for Psalms 10 and 33, the remaining psalms of Book 1 are psalms of David. Most of them are prayers of distress. Others are statements of confidence in the God who alone can save (e.g., 9; 11; 16; 18), striking the note that concludes the book (40–41). Reflections on ethics and worship are found in Psalms 1; 14–15; 19; 24; and 26. |

| Book 2 | Psalms 42–72 | Book 2 introduces the first group of psalms by the “sons of Korah” (42; 44–49; 50). There are also more psalms of David (51–65; 68–69), including most of the “historical” psalms (51–52; 54; 56–57; 59–60; 63). Once again, lament and distress dominate these prayers, which now also include a communal voice (e.g., 44; compare 67; 68). The lone psalm attributed to Solomon concludes Book 2 with a look at God’s ideal for Israel’s kings—ultimately pointing to Christ as the final great King of God’s people. |

| Book 3 | Psalms 73–89 | The tone darkens further in Book 3. The opening Psalm 73 starkly questions the justice of God before seeing light in God’s presence. That light has almost escaped the psalmist in Psalm 88, the bleakest of all psalms. Book 2 ended with the high point of royal aspirations; Book 3 concludes in Psalm 89 with these expectations badly threatened. Sharp rays of hope occasionally pierce the darkness (e.g., 75; 85; 87). The brief third book contains most of the psalms of Asaph (73–83), as well as another set of Korah psalms (84–85; 87–88). |

| Book 4 | Psalms 90–106 | Psalm 90 opens the fourth book of the psalms. It may be seen as the first response to the problems raised by Book 3. Psalm 90, attributed to Moses, reminds the worshiper that God was active on Israel’s behalf long before David. This theme is taken up in Psalms 103–106, which summarize God’s dealings with his people before any kings reigned. In between there is a group of psalms (93–100) characterized by the refrain “The LORD reigns.” This truth refutes the doubts of Psalm 89. |

| Book 5 | Psalms 107–150 | The structure of Book 5 reflects the closing petition of Book 4 in 106:47. It declares that God does answer prayer (107) and concludes with five Hallelujah psalms (146–150). In between there are several psalms affirming the validity of the promises to David (110; 132; 144), two collections of Davidic psalms (108–110; 138–145); the longest psalm, celebrating the value of God’s law (119); and 15 psalms of ascent for use by pilgrims to Jerusalem (120–134). |

https://www.esv.org/resources/esv-global-study-bible/chart-19-03/

Older collections of Psalms can be found within the final arrangement, which probably happened sometime after the Exile. For example, we find psalms of David (3-41); sons of Korah (42-49; 84-85; 87-88); Asaph (50; 73-83); a second Davidic psalter (51-71) and the songs of Ascent (120-134). The Elohistic psalter (42-83) is a collection that includes psalms of Korah, David and Asaph that use the Hebrew word Elohim for God, instead of Yahweh.

Theme and message of the Psalms

I’m not going to outline of the message of the Psalms because I couldn’t improve the Bible Project: https://bibleproject.com/explore/video/psalms/

Your turn:

Psalms 1 and 2 are meant to be read together. Do that now and see if you can figure out why these two Psalms were chosen to introduce the whole collection.

_______________________________________________

*By word count, Jeremiah and Genesis are both longer than Psalms.

**Many psalms contain elements of more than one genre.

Further reading:

https://www.mattstaffordpsalms.com/introduction-to-the-psalms-1